The vortex filament model

The standard vortex filament model (VFM) describes the motion of thin vortex lines in three-dimensional space.

Vortex lines are assumed to be very thin with respect to the scales of interest, such that they can be effectively described as spatial curves.

The Biot–Savart law

In the VFM, each vortex line induces a velocity field around it given by the Biot–Savart law:

where

Mathematically, the above equation derives from the vorticity field:

where

The Biot–Savart law describes in particular the motion induced by vortex filaments on themselves and on surrounding vortex lines. The VFM thus describes the collective motion of a set of mutually-interacting vortex filaments which obey the Biot–Savart law. Note that the Biot–Savart integral is singular when evaluated at a vortex location

Desingularisation

In the VFM, one usually wants to evaluate the Biot–Savart law at locations

The divergence of the Biot–Savart integral is of course unphysical, and is related to the fact that the actual thickness of vortex lines not really infinitesimal but finite. The standard way of accounting for the radius

Here

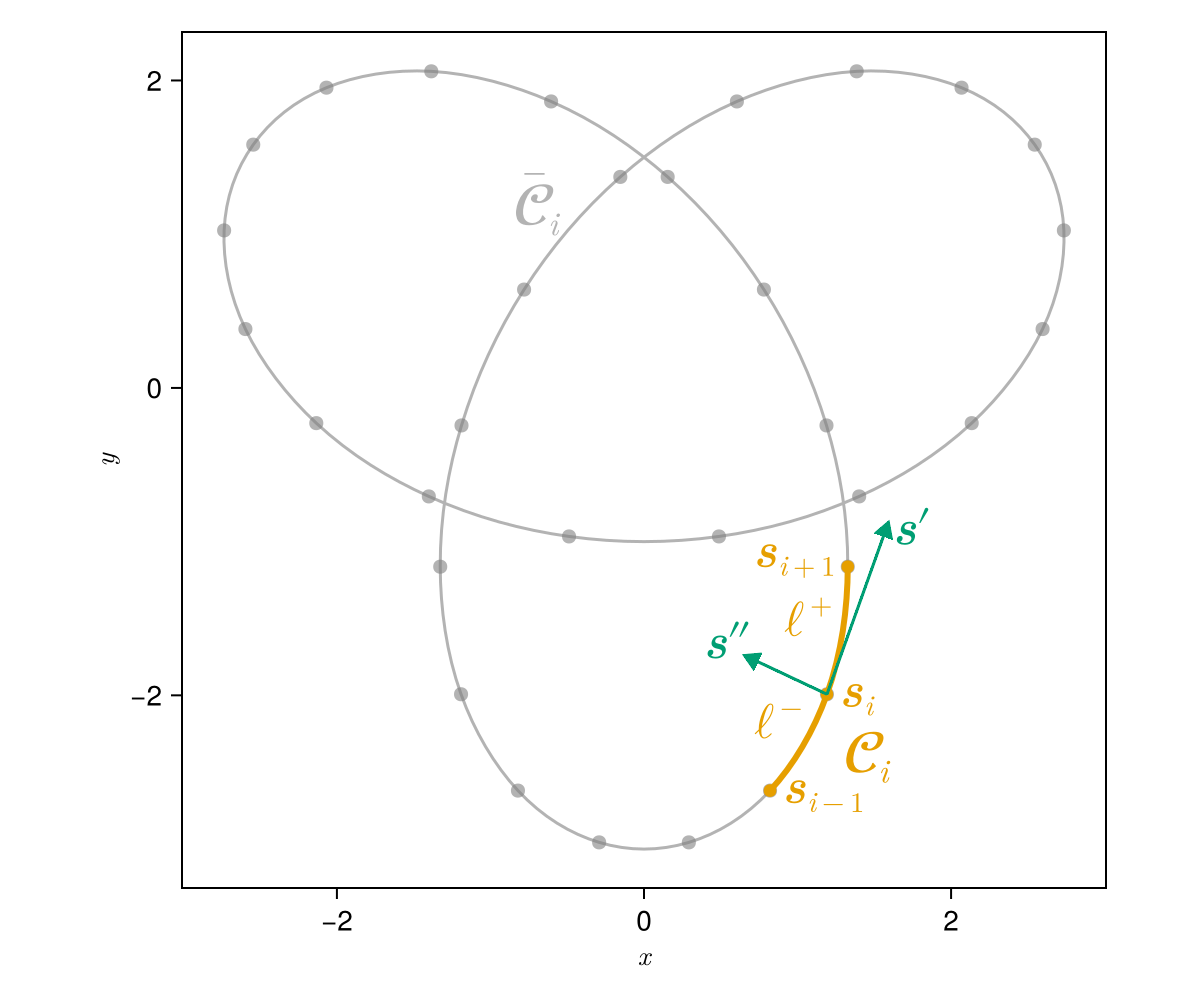

To illustrate this, the figure below shows a trefoil knot curve, or rather its projection on the XY plane. Note that here we represent a discretised version of the curve, where the number of degrees of freedom is finite and controlled by the positions of the markers.

Code for this figure

using CairoMakie

CairoMakie.activate!(pt_per_unit = 1.0)

Makie.set_theme!()

using VortexPasta.Filaments

using VortexPasta.Filaments: Vec3

using VortexPasta.PredefinedCurves: define_curve, TrefoilKnot

trefoil = define_curve(TrefoilKnot())

N = 32

i = (N ÷ 2) + 3

refinement = 8

colours = Makie.wong_colors()

f = Filaments.init(trefoil, ClosedFilament, N, CubicSplineMethod())

fig = Figure(; Text = (fontsize = 24,), size = (600, 500))

ax = Axis(fig[1, 1]; aspect = DataAspect(), xlabel = L"x", ylabel = L"y")

hidexdecorations!(ax; label = false, ticklabels = false, ticks = false)

hideydecorations!(ax; label = false, ticklabels = false, ticks = false)

# Plot complete filament in grey

let color = (:grey, 0.6)

plot!(ax, f; refinement, color, linewidth = 1.5, arrows3d = (;))

text!(

ax, f(i ÷ 2 + 1, 0.6);

text = L"\bar{\mathcal{C}}_{\!i}", align = (:right, :bottom), color,

fontsize = 28,

)

end

# Plot point of interest and local segment around it

let color = colours[2], arrowcol = colours[3]

# Plot nodes (i - 1):(i + 1)

scatter!(ax, getindex.(Ref(f), (i - 1):(i + 1)); color)

text!(

ax, f[i - 1] + Vec3(0.08, 0.0, 0.0);

text = L"\mathbf{s}_{i - 1}", align = (:left, :center), color,

)

text!(

ax, f[i] + Vec3(0.08, 0.0, 0.0);

text = L"\mathbf{s}_i", align = (:left, :center), color,

)

text!(

ax, f[i + 1] + Vec3(-0.08, 0.08, 0.0);

text = L"\mathbf{s}_{i + 1}", align = (:right, :center), color,

)

# Plot local segments

let ζs = range(0, 1; length = refinement + 1)

lines!(ax, f.(i - 1, ζs); color, linewidth = 3)

lines!(ax, f.(i, ζs); color, linewidth = 3)

text!(

f(i - 1, 0.5);

text = L"ℓ^{-}", align = (:right, :bottom), color,

)

text!(

f(i, 0.6) + Vec3(-0.08, 0, 0);

text = L"ℓ^{+}", align = (:right, :center), color,

)

text!(

ax, f(i - 1, 0.7) + Vec3(0.2, 0.0, 0.0);

text = L"\mathcal{C}_{\!i}", align = (:left, :top), color,

fontsize = 28,

)

end

# Plot tangent and curvature vectors (assuming this is a 2D plot...)

s⃗ = f[i]

t̂ = f[i, UnitTangent()]

ρ⃗ = f[i, CurvatureVector()]

lengthscale = 1.2

arrows2d!(ax, [s⃗[1]], [s⃗[2]], [t̂[1]], [t̂[2]]; color = arrowcol, shaftwidth = 1.5, tipwidth = 10, lengthscale)

arrows2d!(ax, [s⃗[1]], [s⃗[2]], [ρ⃗[1]], [ρ⃗[2]]; color = arrowcol, shaftwidth = 1.5, tipwidth = 10, lengthscale)

text!(

ax, s⃗ + lengthscale * t̂;

text = L"\mathbf{s}′", align = (:left, :center), color = arrowcol,

offset = (2, -4),

)

text!(

ax, s⃗ + lengthscale * ρ⃗;

text = L"\mathbf{s}″", align = (:right, :center), color = arrowcol,

offset = (4, 6),

)

end

save("trefoil_local.png", fig)Here, to evaluate the velocity induced by the trefoil vortex on its point

More explicitly, from a Taylor expansion of

where

Now, if one integrates e.g. from

where

where we have taken the cut-off distance to be

In the code, the local velocity is sometimes referred to as the LIA (local induction approximation) term, as it has been historically used as a fast (and incomplete) approximation to the full Biot–Savart integral.

Streamfunction and energy

Everything that has been discussed until now applies to the velocity derived from the Biot–Savart law. Sometimes we may also be interested in the streamfunction vector

Streamfunction from vortex lines

In three dimensions, the streamfunction is a vector field which is directly related to the velocity and vorticity by

That is, if one knows the vorticity field

Using the fact that the vorticity has the form

Note that the usual Biot–Savart law for the velocity can be recovered by taking the curl of the above expression:

where we have used

Connection with kinetic energy

The kinetic energy of the system is given by

where the second equality is obtained using integration by parts and assuming we're in a periodic domain (or, alternatively, that the velocity goes to zero far from the vortices), and

That is, the energy is simply the line integral of the tangential component of the streamfunction along vortex filaments.

Note that, if one uses the expression for

where the prime over the integral is to account for the desingularisation of the streamfunction integral (see section below).

Desingularisation of the streamfunction integral

As for the velocity, the Biot–Savart integral for the streamfunction is singular when evaluated on a vortex line. We can use the same approach to desingularise it, by splitting the integral onto a local and a non-local part.

Using the same notation as for the velocity, a leading-order Taylor expansion of the integrand leads to:

and then to:

Note that, here, the cut-off distance

Example: vortex ring

For a circular vortex ring of radius

where we have defined

Adding the local integrals obtained by desingularisation leads to:

The first expression obtained is the well-known self-induced velocity of a thin vortex ring.

From the second expression, we can easily obtain the energy associated to the vortex ring:

We can finally check that, with the desingularisation procedure described in the previous sections, the vortex ring obeys Hamilton's equation

For a vortex ring,

Noting that

we finally obtain that

Energy in open domains

In open (non-periodic and unbounded) domains, assuming that the velocity field goes to zero sufficiently far from the vortices, a commonly used alternative expression for the energy is (Saffman, 1993):

which only requires knowing the velocity

However, this definition does not satisfy Hamilton's equation, meaning that this "energy" may present fluctuations in time in cases where the previous definition will be conserved.

This can be easily shown for the case of a vortex ring, in which case applying this definition to the expression for the vortex ring velocity leads to

which overestimates the actual vortex ring energy by a

These differences might be explained by the fact that this second definition doesn't take into account the internal structure of the vortices, unlike the first definition which does this via the local contribution to the streamfunction.

References

A classical reference for the VFM is Schwarz (1985), while a more modern review is given by Hänninen and Baggaley (2014). Details on the streamfunction vector, its desingularisation and the choice of cut-off to ensure energy conservation can be found in Polanco (2025).